|

OLD-TIME GUNNERS: THEIR DUCKING MODES. A NOTABLE SHOT. THE

REASONS WHY LESS DUCKS NOW THAN IN EARLIER DAYS. COMMON DUCKS

THEN, NOTABLES NOW. MODES DISCUSSED.

The most efficient and persevering gunners seventy or more years

ago on this Island--I mean those that followed it for a

livelihood--were Wilson Cooper, Thomas Bowden, Timothy Bowden,

aforesaid, Zechy Simpson, Rol Grimstead, Leven Ballance, Fred

Davis, Edmund and Jereman Litchfield, two or three Ansell trained

by Cooper through family relationship, John Dudley and likely some

others.

Of course there were scores of others that followed fowling but

none so constantly as these.

Don't make as mistake and get mixed by taking the Wilson Cooper

and Timothy Bowden who are famous gunners on the Island now, for

the former were the respective parents of the latter two.

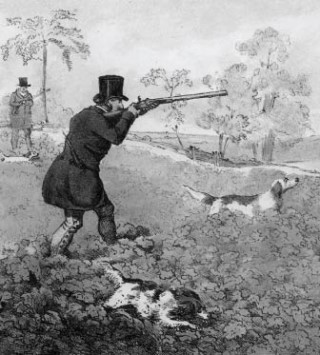

In those days the mode of duck shooting was not as now. Ducks

were shot sitting and at the rise. The crawling practice in vogue.

Go into the marsh with noiseless care; look over the coves, creeks

and ponds; see if any of the feathered tribe have ventured near

enough to shore for a shot; if so, down on hands and knees, often

in mud and water; crawl to the water's edge; peep through the

marginal marsh or galls; see where ducks were thickest.

Ready--aim--bang. Fuss and feathers, what clatter and scramble:

There might be three or four or a score of dead and crippled

ducks. In went the hunter attending to cripples first, often

chasing a wing-break a great distance. He would then gather up his

trophy, return to the shore wet from waist down.

When two hunters were together, often one would shoot at the

sitting the other at the rise or flirt.

If the flock were sprigtails, which feed with tails up, heads

down, the most of those left after a shot would be cripples. To

avoid this, it was custom to give a keen whistle so that the old

duck policeman, sitting off a good distance, keeping watch over

its flock, would give the warning quack and flirt: immediately

heads up--bang, bang at the flirt.

The guns used then were English and French muskets, about as

large as the modern No. 10, and were of the flint-and-steel,

cock-and-pan make.

These guns often missed fire, especially in damp weather. The

steel being dampened the flint would fail to knock fire in the

pan; and if it did, the powder in the pan might be moist or

corroded about the touchhole, then there would be a missfire--"a

flash in the pan" as it was called. If this occurred when a good

bunch of ducks was in front likely some cuss words against gun and

powder would be uttered by some, mumbled by others.

To be sure the next time, the dry part of the woolen coat tail or

the under part of the sleeve was applied to the steel till it

glittered; the flint ragged with jackknife; touchhole opened; dry

powder put into the pan with dry tow thereon and clamped down;

then gun lock under coat-tail and arms, the hunter was off for

better luck.

The marshes were interspersed with coves, ponds and creeks, where

if permitted, ducks frequented nights, to feed and rest; these

furnished other of duck hunting: On the east side of pond or cove

before night; build a blind so that the reflection of the

departing sun glazed a path to the west; lie down and wait the

coming. Whir,--down-flat;--pish-shu-u. If near dark and the ducks

swam across this glazed path,--bang. This went on from sun-down

till dark. A chance shot from an expert might kill in the dark.

Those who followed this mode seldom went home without a mess of

ducks.

Wild geese tamed or raised and also ducks raised on the premises

were used in those days for decoys; and in strong westerly winds

and a high tide, with these geese decoys, two persons would often

kill a hundred geese in one day at the margin of the sand-beach or

on some conspicuous shoal nearby. With tame decoy ducks near

marshy Islands or points they often did well. This was before the

modern wooden decoys were known.

A NOTABLE SHOT,

The old man Zechy Simpson made one of the most notable shots ever

made on the Island, and it is doubtful if it was ever surpassed

anywhere with a common shoulder gun. He lived on a point of land

that jutted into the bay. In a certain hard freeze there was an

air-hole near his house; the ducks were so thick in that open

space there was not room for the hundreds that, failing to get in,

still hovered around. He charged his old musket, went down, and

drew a bead on them, and killed forty seven malard ducks that he

got, while some others dropped on the ice which he failed to get.

This air-hole ran from the shore outward, and while he was

gathering up his forty-seven ducks some criples went ashore, and a

boy by the name of Henry Bright, who lived with Mr. Jesse White

near by, went directly afterward and got five more that had come

ashore, making fifty-two in all from that one shot. It was said

there were a few black ducks among them, if so, they didn't lessen

the magnitude of the shot for both blacks and malards are very

large ducks.

This is no fiction, but a true story.

Ducks and geese in those days were in solid rafts. One bitter

cold Sunday, the writer with others, was on the bayside up in

Jones's wind-mill; the wind was blowing a galefrom west; the ducks

and geese ran from the fence locks out for a hundreds of yards,

wedged so closely together that scarcely any water could be seen

among them; but not one man among the half dozen present would

dare shoot them on the Sabbath, although there were guns in the

miller's house. How would it be now.

I have seen many larger rafts than the one spoken of above, in

Knotts Island Bay and its adjacent shoals and Swan Island (once

called Crow Island) waters. When they were distrurbed and arose

the noise made was like distant rumbling thunder.

The honk of geese, the clatter of ducks mixed with the sonorous

tune of the swan, all quickened by fright, made a deafening din.

The large raft would go and join another and this would be

repeated every time they were disturbed.

It is amusing to hear some people at this day say, there are as

many ducks frequenting our waters now as ever in years past. Now

the writer will say right here, that during any winter now there

cannot be over twenty-five per cent of the fowl that frequented

our waters seventy years ago. There may be as many killed now as

then, more money realized, but this does not prove that there are

as many ducks now as then. Seventy years ago our country was

thinly populated: our gunners used the old flint-and-steel muskets

to kill ducks; crawling, killing and wading waist deep after them

was the mode the kind of duck then sought for family use and to

supply a small near by market was what is now called common The

few killed for sale then were dragged through mud and mire with

team and cart miles away, and for a small price. The ducks in

those days had only to watch the margin of coves, creeks, ponds,

bays and other shore lines for the shooters.

Now let us see why the millions of wild fowl that once swarmed

our waters have wonderfully decreased--all but disappeared.

There are fast lines of steamers and railroads that care little

for distance; these and most all commercial houses have

refrigerators to keep ducks from taint; with the product of the

ice plant ducks can now, if needed, be kept for months as hard as

a rock.

The population of the United States has immensely increased;

hamlets and villages have grown to large cities; the then cities

have grown in population till some have passed the million mark;

the whole country has increased about in the same proportion.

So there is a market for everything; a person living away back

in the country may order a mess of ducks from these market cities

and have them conveyed to him in a jiffy.

Now, as to the latter-day mode of slaughtering the fowl that

still venture to visit us in winter: They scarcely have the

privilege of flying within one hundred yards of the surface of the

water. There are numerous boxes, called "batteries," sunk even

with the surface of the water, with floating wings water-colored,

riding the billows; the gunner crouched in box, surrounded by

hundreds of wooden decoys, with few iron ones perched on box for

ballast as well as to deceive. Here comes a flock of deceived

birds and if they approach within one hundred yards in air, a part

of this flock is likely to come down after several explosions from

that box. If this box does not sweep them all there are fifty

other boxes and blinds in their path to hammer the life out of

this little venturesome flock. I have frequently been informed by

gunners that wild fowl, finding no resting place on the feeding

grounds in the day time, have to betake themselves to the Atlantic

Ocean and sit there resting on its swells till night, when they

venture back, to stop hunger: even then they are killed by some

fire-lighting dare-devils.

This mode of killing fowl in Currituck prevails throughout this

land of ours where wild fowl abound.

Now, let me give the unvarnished truth why wild fowl in Currituck

as well as elsewhere are becoming scarcer and scarcer.

This country has six times the population that it had when the

writer was born. There are millions of wealthy people of

speculative habits roaming the country, some for pleasure, some

for both pleasure and lucre. Among these are many sportsmen with

gun and tacklings, hundreds of thousands of them. These hunters

hail from everywhere, and go where ever wild birds or beasts are

found, especially so, in the United States and the British

Possessions. They not only kill these birds, but go North in the

frozen zone during Summer where these birds lay their eggs,

encamping themselves for the season, and live on their flesh.

While many make it a lucreative business by securing the feathers,

others stuff and preserve the feathered skins to sell to curiosity

seekers; others, still, collect millions of eggs, preserve them by

modern processes, and sell them in the markets when cold weather

comes.

Then why should there be as many now as then? There is every

reason to the contrary. In his youth the writer could see in two

miles square, more ducks then than can now be seen in going from

Vanslyck's to the Virginia line. If these brooding places North

are not protected, soon there will be neither ducks nor other like

birds to visit us. As I have said before the ducks sought in those

days were what are now called "common," such as sprigtail, black,

creek, mallard, ball-pate, blue-wing, teal and some others.

In those days little notice was taken of the canvasback and

red-head (then often called "bull-necks"); and as to the booby,

now grown so famous, a raft at hand would not have enticed a shot;

they were considered a nuisance; once in a while the boys would

take a shot at them for fun, to see them dive at the flash.

The canvas-back and red-head were not very plentiful in the

shallow waters frequented mostly by oldtime gunners, but they

would be found in large numbers in the deep water of the sound and

on its margin; also, in the deep, muddy waters of Bellow's Bay and

Back Creek. It did not pay to seek these now famous ducks, which

involved in shooting them at long range and wading to the armpits

after them; there were plenty of the common ones to be had with

far less trouble. Furthermore, these two notables could dive at

the flash, as well as the booby. These famous Bull-necks were

always sold in Norfolk; one dollar was the maximum price for the

canvas-back, about one half to three quarters of that price for

red-heads, and usually from twenty-five to fifty cents for a pair

of the common ones. So it did not pay to hunt for a pair of

bull-necks when perhaps a dozen pairs of the common ones could be

had with much less trouble.

But few of the old-time hunters purchased powder and shot by the

keg and bag; some like Cooper, Bowden, Simpson I and some others

may have done so; but the majority sent to Norfolk for ammunition

in small quantities, when it could not be had at the Island shops.

Those shops could often furnish the majority of small gunners

with ammunition. The call would invariably be: Half pound powder,

two pounds shot. By a peak in my makeup, I hear that call yet.

Back to the top.

|